Considerable

debate exists with regard to the relationship of the Indus Valley civilization

and the later Vedic tradition that focused on fire worship. The scholarly

consensus for many years held that the Aryans, people who migrated from the

west through Iran, arrived in India no earlier than 1200 B.C.E., much too

recently to have participated in the Indus Valley world. These people were, the

view holds, associated with the transmission of the Vedas, India’s most sacred

and revered texts. This consensus has been challenged, primarily from the

Indian side, and continues to undergo scrutiny. The alternative view rejects

the notion that the people who gave India the Vedas were originally foreign to

India and sees a continuity between India’s earliest civilization and the

people of the Vedas.

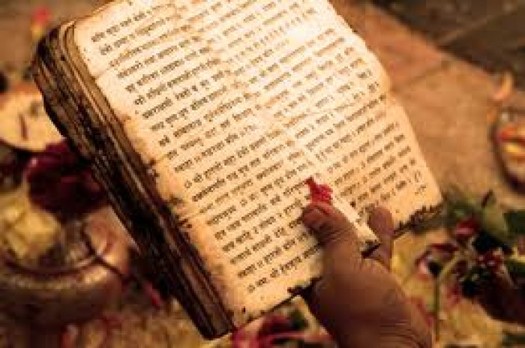

The

Rig Veda (c. 1500 B.C.E.), which everyone agrees is the most ancient extant

Indian text, is the foundational text of Hinduism. It consists of about a

thousand hymns. The great majority of the hymns are from five to 20 verses in

length. The Rig Veda contains hymns of praise to a pantheon of divinities as

well as a few cosmogonic hymns that tell of the creation of the universe. These

stories are extremely important for the development of later Hinduism.

By

far the greatest number of the thousand plus hymns of the Rig Veda are devoted

to Indra, king of the gods, a deity connected with rain and storms who holds a

thunderbolt, and Agni, the god of fire. The rest of the hymns are devoted to an

array of gods, most prominently Mitra, Varuna, Savitri, Soma, and the Ashvins.

Less frequently mentioned are the gods who became most important in the later

Hindu pantheon, Vishnu and Rudra (one of whose epithets was shiva, the benign).

A number of goddesses are mentioned, most frequently Ushas, goddess of the

dawn, and Aditi, said to be the mother of the gods. The goddess of speech, Vach

(Vak), however, may be most important, since speech is one of the most powerful

sacred realities in Hindu tradition, although there are not many references to

her.

The

religion of the Rig Veda has for a long time been referred to as henotheistic,

meaning that the religion was polytheistic, but it recognized each divinity in

turn as, in certain ways, supreme. Certainly, later Hinduism continued and

enriched this henotheistic concept, and, through time, Hinduism has been able

to accept even Christ and Allah as being supreme “in turn.” The Rig Veda,

though, was the central text in a very powerful ritual tradition. Rituals

public and private, with sacred fire always a central feature, were performed

to speak to and beseech the divinities. Sacrifices of animals were a regular

feature of the larger public rites of the Vedic tradition.

Two

other Vedas, the Yajur and Sama Vedas, were based on the Rig Veda. That is,

most of their text is from the Rig Veda, but the words of the prior text are

reorganized for the purposes of the rituals. Yajur Veda, the Veda of

sacrificial formulas, which has two branches called the Black and the White

Yajur Vedas, contains the chants that accompany most of the important ancient

rites. The Sama Veda, the Veda of sung chants, is very much focused on the

praise of the god Soma, the personification of a drink taken at most rituals

that probably had psychedelic properties. Priests of the three Vedas needed to

be present for any larger, public ritual. Later a fourth Veda, the Atharva

Veda, became part of the tradition. This text consists primarily of spells and

charms used to ward off diseases or to influence events. This text is

considered the origin of Indian medicine, the system of Ayurveda. There are

also a number of cosmogonic hymns in the Atharva Veda, which show the

development of the notion of divine unity in the tradition. A priest of the

Atharva Veda was later included in all public rituals and the tradition evolved

to include four Vedas rather than three.

Two

important points must be understood about the Vedic tradition. First, none of

the Vedas is considered composed by humans. All are considered to be “received”

or “heard” by the rishis, divinely inspired sages, whose names are noted at the

end of each hymn. Second, none of the text of the Vedas was written down until

the 15th century C.E. The Vedic tradition was passed down from mouth to ear for

millennia and is, thus, the oral tradition par excellence. The power of the

word in the Vedic tradition is considered an oral and aural power, not a

written one. The chant is seen as a power to provide material benefit and

spiritual apotheosis. The great emphasis, therefore, was on correct

pronunciation and on memorization. Any priest of the tradition was expected to

have an entire Veda memorized, including its non-mantric portions.

Any

of the four Vedas is properly divided into two parts, the mantra, or verse

portion, and the Brahmana, or explicatory portion. Both of these parts of the

text are considered revelation, or shruti. The Brahmanas reflect on both the

mantra text and the ritual associated with it, giving very detailed, varied,

and arcane explication of them. The Brahmanas abound in equations between

ritual aspects, the ritual performers, and cosmic, terrestrial, and divine

realities. Early Western scholars tended to discount these texts, as being

nothing but priestly mumbojumbo. But most recent work recognizes the central

importance of the Brahmanas to the development of Indian thought and

philosophy.

The

name Brahmana derives from a central word in the tradition, brahman. Brahman is

generically the term for “prayer” but technically refers to the power or magic

of the Vedic mantras. (It also was used to designate the one who prays, hence

the term Brahmin.) Brahman is from the root brih, “to expand or grow,” and

refers to the expansion of the power of the prayer itself as the ritual

proceeds; this power is understood as something to be “stirred up” by the

prayer. In later philosophy, the term brahman refers to the transcendent, all-encompassing

reality.

The

culmination of Brahmana thought is often considered to be the Shatapatha

Brahmana of the White Yajur Veda. It makes explicit the religious nature of the

agnichayana fire ceremony, the largest public ritual of the tradition.

Shatapatha Brahmana makes clear that this public ritual is, in fact, a

reenactment of the primordial ritual described in Rig Veda X. 90, the most

important cosmogonic hymn of the Vedas. This myth describes the ritual

immolation of a cosmic “Man,” whose parts are apportioned to encompass all of

the visible universe and everything beyond it that is not visible. That is, the

cosmic “Man” is ritually sacrificed to create the universe. Shatapatha Brahmana

delineates how, at the largest public ritual in the tradition, the universe is

essentially re-created yearly. The Brahmana understands that, at its most

perfect, the Vedic ritual ground is identical to all of the universe, visible

and invisible.

Within

the Brahmanas two subdivisions are important in the development of later

tradition. One of the subdivisions is called the Aranyaka. From its name one can

understand that this portion of the text pertained to activity in the forest

(aranya). These specially designated portions of the Brahmanas contain evidence

that some Vedic yajna, or ritual, was now performed internally, as an esoteric

practice. This appears to be a special practice done by adepts, who would

essentially perform the ritual mentally, as though it were being done in their

own body and being. This practice was not unprecedented, since the priests of

the Atharva Veda did not chant as other priests, but rather were required at

public rituals to perform mentally the rituals that other priests performed

externally. But the Aranyaka notion was distinctive in that the ritual was

performed only internally. From this interpretation originated the notion that

the ritualist himself was the yajna, or ritual.

Last,

the Brahmanas included (commonly within the Aranyaka portion) the Upanishads,

the last of the Vedic subdivisions or literary modes (no one really knows when

these subdivisions were designated). As do the Brahmanas, many of these texts

contained significant material that reflected on the nature of the Vedic

sacrifice. Thus, the division between Brahmana proper, Aranyaka, and Upanishad

is not always clear. The most important feature of the Upanishad was the

emergence of a clear understanding of the unity of the individual self or atman

and the all-encompassing brahman, understood as the totality of universal

reality, both manifest and unmanifest.

The

genesis of the Upanishadic understanding, that the self and cosmic reality were

one, is clear. First, the Shatapatha Brahmana stated that the most perfect

ritual was, in fact, to be equated to the universe itself, visible and

invisible. Second, the Aranyakas made clear that the individual initiated

practitioner was the ritual itself. So, if the ritual equals all reality and

the individual adept equals the ritual, then the notion that the individual

equals all reality is easily arrived at. The Upanishads were arrived at, then,

not by philosophical speculation, but by ritual practice. Later Upanishads of

the orthodox variety (that is, early texts associated with a Vedic collection)

omitted most reference to the ritual aspect and merely stated the concepts as

they had been derived. Most importantly, the concepts of rebirth

(reincarnation) and the notion that actions in this life would have consequence

in a new birth (karma) were first elaborated in the Upanishads.

This

evidence shows that the concept of karma, or ethically conditioned rebirth, had

its roots in earlier Vedic thought. But the full expression of the concept was

not found until the later texts, the Upanishads, which are called the Vedanta,

or the end or culmination of the Vedas. Therefore, the notion of reaching unity

with the ultimate reality was seen as not merely a spiritual apotheosis, but

also a way out of the trap of rebirth (or re-death).

Comments

Post a Comment